Derek Jarman, visionary filmmaker, artist, writer, activist, my hero, died 30 years ago this week.

I first heard about Derek Jarman through the work of Brian Eno. One of the first albums I bought when I started listening to Eno in the mid-1990s was his soundtrack for Jarman's last film, which was subsequently reworked by Jah Wobble and released as the underwhelming Spinner. That last film of Jarman's was Glitterbug — a great, mischievous title — and was a compilation of his Super-8 films from the 1970s and 1980s. He never saw it finished.

Jarman is primarily known as a film-maker, but if I'm honest I'm not that big a fan of his films.

Blue is, of course, a defining work, and his Super-8 film work had an obvious influence on the promotional videos I've made for Out of Season.

His film Wittgenstein, shot against a black backdrop, within which the actors and key props are placed (theatre-style) is an example of budgetary constraints working to artistic advantage — proof of Brian Eno's dictum that “If you want to get unusual results, work fast and work cheap, because there's more of a chance that you'll get somewhere that nobody else did. Nearly always, the effect of spending a lot of money is to make things more normal”.

You could never accuse Wittgenstein of looking “normal”:

But it's his writing that speaks to me the most. Anyone reading him must feel the same incredible sense of intimacy with the voice speaking there. You want to reach out to him; he’s so vulnerable, and courageous, so unfairly vilified. You want to call him Derek.

In 1986, shortly after his HIV diagnosis, he bought Prospect Cottage, a fisherman’s shack in the shadow of Dungeness nuclear power station. In Modern Nature, my favourite book of his — the only book I’ve read ten times— he intertwines reflections on his creation of a garden at the cottage, with musings on health, creativity, and mortality.

Dungeness — Britain's sole desert — is about as unlikely a habitat for a botanist as you can imagine. It is a microclimate of extremes, marked by drought, fierce winds, and corrosive sea-salt, which frequently damaged his plants.

But amidst this rocky expanse, overshadowed by the looming nuclear facility, Jarman dug deep into the shingle and crafted an unlikely sculptural garden out of hardy flaura and various bits of repurposed flotsam that he found washed up on the Ness’s shoreline.

Modern Nature invites you to look closer at the landscape, the same way that Derek — who had initially dismissed the area as barren — had only started to notice the unexpected abundance of flora and fauna that Dungeness supported after he had moved in.

The language he uses in Modern Nature guides you into this closer inspection — and seems, somehow, to breathe life into the landscape, transforming what might appear desolate or inhospitable into a kind of paradise teeming with life.

Derek's descriptions are not merely factual, but are imbued with a poetic resonance, dancing with the rhythm of the seasons, and capturing the ephemeral beauty of blooming flowers, the delicate flutter of butterflies, and the ever-changing hues of the sky.

The book brimms with lists of flora: purple iris, borage, houseleeks, sedums, horned poppy, sea kale, dianthus, saxifrage, forget-me-nots, sempervivum, clove-scented gillyflowers, bluebells, calendula, santolina, mullein, viper’s bugloss...

I barely know what half of these things are, if I'm honest, and I don't care; the litany of beautiful names is enough. Modern Nature is a kind of ambient book (back to Eno again, as always); you don't read it for horizonal movement, for plot, or development — you read it for the mood it creates; you read it to immerse yourself in that world, for a while.

Tuesday 7

The rain and fine warm weather have quickened the landscape — brought the saturated spring colours early. The dead of winter is passed. Today Dungeness glowed under a pewter sky — shimmering emeralds, arsenic, sap, sage and verdigris greens washed bright, moss in little islands set off against pink pebbles, glowing yellow banks of gorse, the deep russet of dead bracken, and pale ochre of reeds in clumps set against the willow spinney; a deep burgundy, with silvery catkins and fans of ochre yellow stamens fringed with the slightest hint of lime green of newly burst leaves.

This symphony of colour I have seen in no other landscape. Dungeness is a premonition of the far North, a landscape Southerners might think dreary and monotonous, which sings like the birch woods in Sibelius' music…

Monday 28

Eno's “On Land” is the music of my view: a crescent moon under a dog star, clouds scudding in the grey dawn.

It’s a beautiful read; buy it now, if you haven’t read it — you’ll thank me later.

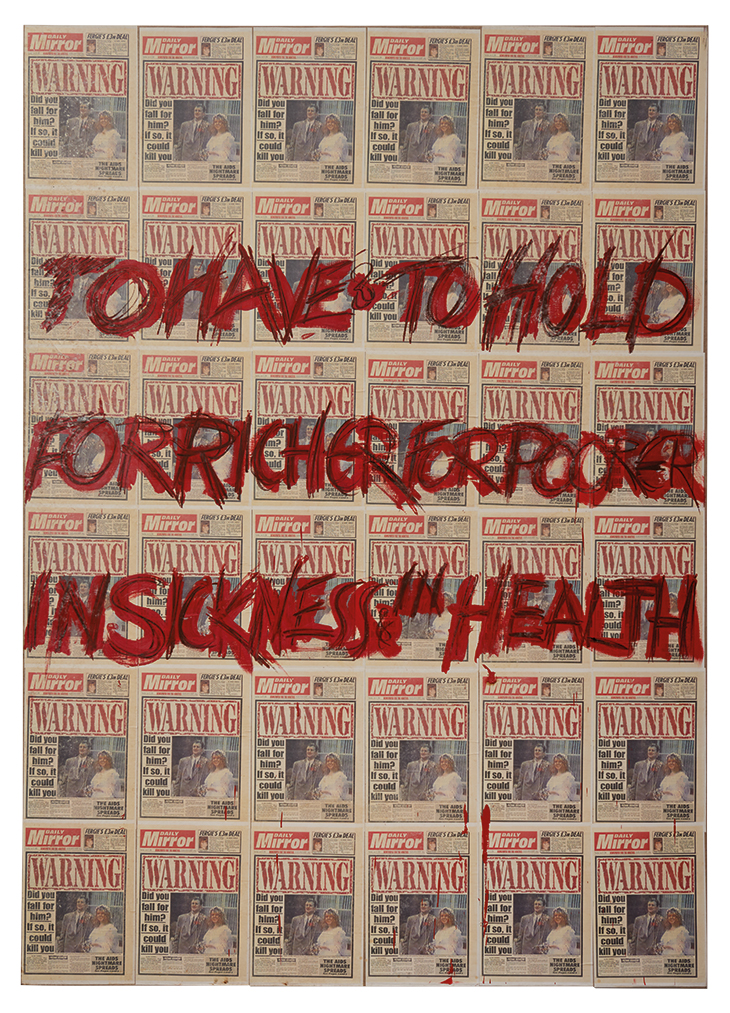

Of course, beyond his contributions to the arts, Derek was an advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and HIV/AIDS awareness, and Modern Nature, as well as being beautifully written, also fizzes with anger.

Derek was enraged by the discrimination surrounding HIV, the suppression of information about the epidemic, and the inadequate research and funding that went into tackling the spread of the virus. He used his platform both to raise awareness about the AIDS crisis and to combat homophobia; his advocacy helped to destigmatize the virus and played a crucial role in shaping public perception and policy responses to the epidemic.

Mixed in with all of this is a sense of frustration with England, and a yearning to return to a more expansive, more diverse, less jingoistic idea of what England — then in the throes of the Thatcher Revolution — could be. Like many, Jarman abhored the New Right's combination of ultra-liberal economics, with extremely restrictive morality, and felt that the emergence of AIDS had normalized levels of homophobia not witnessed since the 1950s.

And yet despite this (or perhaps because of it) he retained a deep, unwavering, almost idealistic love for England — albeit a kind of love clouded with disappointment and criticism.

His mixed feelings about England come across in Modern Nature, and the films he was making around this time (The Last of England and The Garden) — the same strand of thinking in Derek's work that I was drawing from when I was making my recent album, Out of Season.

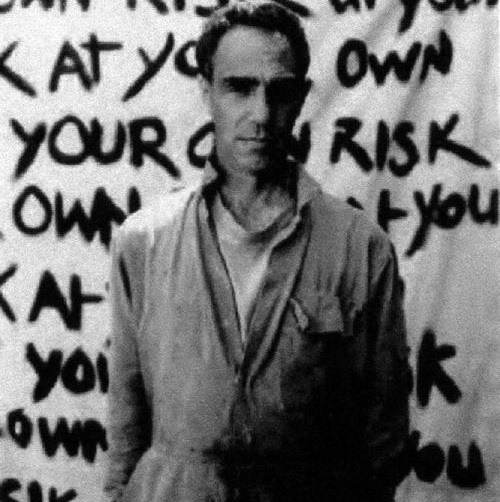

As one of the first genuinely famous people to come out as HIV positive, he was a regular target for tabloid ire, grimly noted in Modern Nature, and reflected in his later paintings — but throughout, he remained charismatic, humorous, and brimming with mischief. Here he is, dealing with a photographer from The Sun, in 1989:

A letter from the Folkestone Herald alerted me: the Sun wanted to buy their photos of me.

Meanwhile the lawyers' letter to the People and the Mirror have produced an apology and a correct reporting of my HIV status under the headline 'Del's Not Dying'…

A motorbike draws up and a hapless reporter from the Sun clambers off. This is his third trip down here from London.

"Do you mind if I photo you?"

"Yes, but since one way or another you're going to, we might as well do a good job of it" […]

I fix him with a basilisk stare as he clicks away.

"You look uncomfortable", he remarks.

"Not as much as you should".

"Oh?"

"I'm writing a diary, which I'm publishing. You're today's entry. When all is said and done what I choose to write will, I expect, be the only trace of your life. Your memory is in my hands".

Long silence.

“The Sun's not kept by the British Museum; the paper destroys itself, it's so acid. When you get back, tell your editor to read the retraction in the People. Because the next time I'm going a million...”

In his later years, he said he had two aims: to outlive the Thatcher government, and to survive AIDS. He achieved only one of those, of course; effective treatments for AIDS came along two years after he died.

I can only imagine what he would have created, had he survived, or what he would have thought of the last 30 years; what he would have thought of gay marriage; whether he would have thought it remarkable that HIV was survivable; what he would have thought of things like Brexit. He was a complicated man, with counterintuitive feelings about things; his opinions may well have surprised us.

Filmmaker; writer; poet; designer; gardener; painter; sculptor... he transcends the boundaries of medium, and reminds me that it's not dexterity nor technical skill that makes an artist, it's the sensibility.